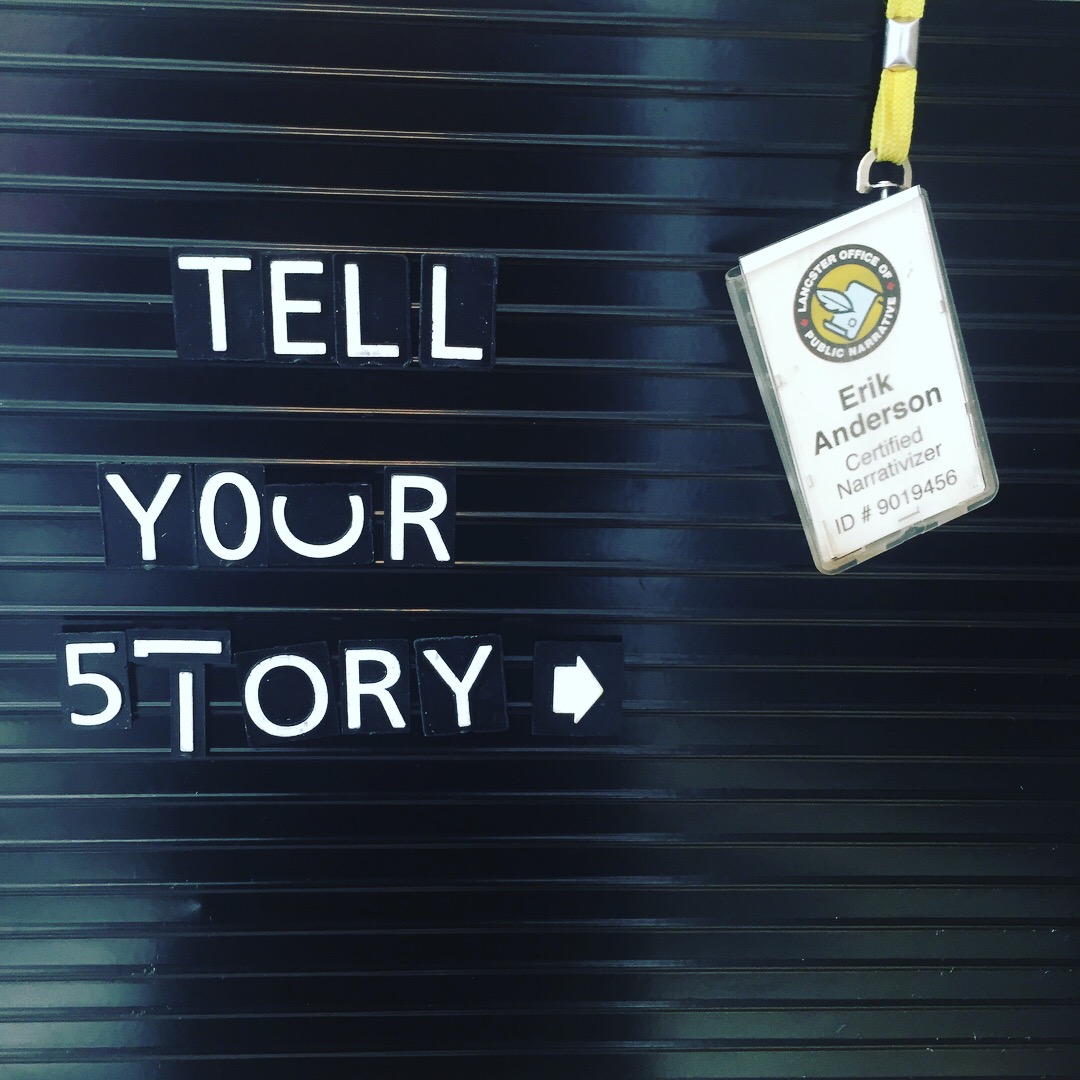

Museum of the living worker: LAncaster office of public narrative

"NOTICE….that the stories people tell about a place tell the story of that place is a less straightforward notion than it seems. History may be one thing, and marketing another, but experience is so often something else—and narrative something more." - Erik Anderson

On a hot and sticky week in July, writer and professor Erik Anderson set up the Lancaster Office of Public Narrative (LOPN) in the Museum of the Living Worker.

Erik, as the Chief Narrativizer at the LOPN offered 20-minute narrative consultations. After listening to passer-by's best, worst or weirdest Lancaster story, Erik processed and edited each conversation into a highly memorable, easily digestible version of 100 words or less. All sessions were free of charge. Each participants received a small honorarium and finalized stories were delivered to their narrativees via USPS on official LOPN letterhead.

Peruse some of these fascinating Lancaster bits below ....

- NOTICE -

That the stories people tell about a place tell the story of that place is a less straightforward notion than it seems. History may be one thing, and marketing another, but experience is so often something else—and narrative something more.

It was to honor and explore that difference that during the week of July 22, 2018, the Lancaster Office of Public Narrative (LOPN) occupied Modern Art’s Museum of the Living Worker. Residents were invited to tell their best, worst, or weirdest Lancaster stories. Participants were paid. When the week was over, LOPN really got to work, condensing and retelling the stories it had heard.

In the interest of privacy, and in the interest of favoring wholes over parts, LOPN has chosen to print these stories anonymously, that this may be a collective portrait. LOPN would be remiss, however, not to thank the participants without whose humor and insight and generosity of spirit this portrait could not have been produced.

- 1 -

When the knock came, she had only been in the house a couple of days, pregnant, alone, surrounded by boxes. In D.C., the only person she had known on her block was a woman with a white dog whose name may or may not have been Anne, which may or may not have been spelled with an e. She had been looking for something different, but when her new neighbor left, having told her life story, she touched the tops of each blueberry muffin. Then she called her husband at work. Still warm, she told him, but did he think they were safe?

(scroll down for more...)

3 -

He’d been raised to be a good Zionist, so it was odd as an adult, and almost an atheist, to be rebelling in this way, attending Friday prayers nearly every week. Muslims, he was surprised to learn in Lancaster, a place he had rarely seen any, had hearts and minds and more. The imam had drawn him in, asking, his first night, what mercy, humility, and charity might tell a person about how to vote in an election lacking all three. Would he convert, his equally Jewish wife wondered, and he thought, for several months, maybe.

- 6 -

I’d only been in the country a week and a half, but I took a math test that day. I’d never even studied in a building before. The teacher gave us the formulas and a calculator. In the camp, that would have been cheating. In the camp, the older kids would finish a grade then teach what they’d learned to the younger ones. In the camp, the library was a shelf. Here, it was a room with books and computers. I still remember the feel of the keys on my fingers, the brightness of the screen. Everyone, it seemed, already knew everything. It was horrifying. But I knew that the things that scared me would save me, if I could only figure out how they worked.

- 12 -

Sometimes she imagined how it would sound from his perspective, how he would tell the story of the white woman at the corner of Water and Conestoga, and then again at Conestoga and Prince. Maybe he’d admit to almost killing her at the first corner, or wanting to at the second. Maybe he’d admit to feeling surprised when, having cursed her in Spanish, she did the same right back. His version couldn’t include her call to the police, her ambivalence about the cameras that caught the exchange—she on her bike and he in his Honda—but couldn’t zoom in on his plate. Who did she think she was, he might say. Sometimes she wondered herself.

- 13 -

Once upon a time there was a city, and in that city a family. The family loved the city, but the city didn’t love them back. One day, in the distance, a corporate job appeared, beckoning the family forward. In the new city, the corporate job promised, there would be neighbors who put your trashcans away, alleys your kids could own. There would be yards and bikes and barbeques, dogs and daytrips and ice cream. Years later, although the family couldn’t foresee it, the corporate job would turn on them, or them on it. And yet, job or not, they would stay. For the new city would love them back.

- 14 -

It will always have happened like this. We will always have said goodbye to the surrogates only to find them running things the next day. We will always have stayed up drinking, taking pictures of the TV, as though documenting the reality that will always have outpaced our comprehension. And in the morning, too surprised to be delirious, too stunned for a hangover, it will always have seemed, and will seem again, that everything has changed while staying exactly the same: the wood-paneled walls, the stacking folders, the friend whose eyes you will continue to have met, just for a moment, amid the huddled aides and hurried secretaries, as though to acknowledge that no, nothing is the same, and you will always never know what it meant.

- 20 -

He was an old-fashioned racist, I’d heard, who didn’t want his son dating black girls. But now that son was in a coma, and he looked hard at my hand before shaking it. I would stay away when he was there, or he would exit when I entered. It couldn’t continue, I realized. He knew it too. So one night, as a gesture, I bought him some Victory, his favorite beer. He took it and drank it and the next day he hugged me. He sobbed. It wasn’t reconciliation. It was a hug in a hospital room. His tall, freckled son would soon be awake and yelling at the nurses. We broke up of course, not long after.

- 23 -

I still have the picture on my phone: his crisp white shirt, his bright, broad smile. He was younger then, less grey, but calm and suave as always. I’d grown up in a small Ohio town where the mayor was the principal but also the Methodist priest. But now history was barreling down the track, stopping at the station in my adopted home. An old friend from the small college I’d attended, on the same street where I was born, whisked us into the lobby. The secret service surrounded him, the man who, in seven months, would become the forty-fourth president. My old friend took the picture. I held my young son in my arms.

- 24 -

This would have been maybe ’48 or ’49, at the old farm out where Hunsecker meets Mondale road. Fritz, she said, we need meat for winter, and she grabbed her Colt 45, slipping it into her holster. Down the hill through the fences to the pasture she led me, hand in hand. She was a woman of tremendous will, who had singlehandedly saved the family during the depression—baking and cooking and selling flowers, raising Scotties, preserving eggs. She taught me how to neuter a rooster, how to trap a muskrat, how to build a raft. It was a different place then. We used to hunt pheasants in the field where the Kmart was, an when I was first married I lived in a clapboard house where the Whole Foods is. I remember Granny walked up to the sheep and, in one smooth motion, drew her pistol to its head and fired. We dragged it out of the pasture. Back up the hill. Through the fences. We hoisted it from the roof of the garage, where we sheared it and slaughtered it. The entrails stained the floor.